The tendency in the twentieth

century toward specialization and reductionism lead to a separation of the

Flemish and Italian schools and their dismantling, which made their inherent

flaws manifest. The Flemish school grounded the Italian school’s conception

of forms in nature and the Italian school brought understanding to the

perception of the Flemish school. When they were separated, however, the

Italian school departed into and increasingly abstracted, Platonic conception

of form detached from an observation of nature. Though the Italian and Flemish

schools offer the art student valuable insights into perception and the

understanding of forms, they tend to draw them away from a deeper study and

perception of the natural world.

During the Italian Renaissance the

Platonic Academy of Florence, founded by Lorenzo D’ Medici, and the Platonic

writings of Fichino had a great effect on many artists, particularly

Michelangelo. Art students were encouraged to copy classical sculpture in

order to develop an understanding of the conception of form and design, but

discouraged from copying nature too closely. Soon, however, a Platonic

ideal conception of form, based on an academic idealization of the work of

Raphael, took the place of close perception.

The Flemish school, on the other

hand, through the influence of John Ruskin, developed an increasingly

superficial view of painting and perception that "presents itself to your

eyes only as an arrangement of patches of different colors variously shaded."

This view of art inspired Seurat and the French Impressionists, but it also not

only entailed an abandonment of form but also reality. Behind Ruskin’s

insights into perception lay the radical idealism of Bishop Berkeley and Hume,

which denied the existence of an external reality beyond perception, and the

unity of objects beyond a kaleidoscope of colours, and texture. This

perception was also entirely subjective; so that one could never be certain

that anyone else shared the same perception or would connect attributes the

same way into objects.

This decline in representational art

mirrors a decline in ontology. Ultimately, this approach to perception leads to

the type of ontological relatitivity seen in Quine’s view of language, which is

really just a new form of solipsism. To break this solipsism, we need a common

reference point for meaning. Simply pointing to things in nature, as

Quine shows in “Word and Object”, with his imaginary word “Gavagai”, creates

problems for defining meaning. From the ancient cave paintings, and

pictographs, images and communication, language and art have been intimately

bound, with the picture being the common reference point of meaning. As

children, our ability to distinguish different objects or animals owes more to

the illustrations in our picture books, than it does to our understanding of

Platonic forms or Aristotelian essences. But often these early images remain in

our memory and they become a barrier to a deeper perception of nature.

Any school of painting should

be judged in its ability to bring the artist into a deeper perception and

understanding of nature. Having taught art for many years, I realized that the

reason most students have great difficulty drawing is because they try to draw

some mental conception rather than the scene before them. In the same

way, we tend to replace an authentic experience of nature with some model,

memory or image that reflects our own preoccupations or desires or we cultivate

tame and prune nature to suit our own designs.

We have created a variety of models, metaphors, and

narratives for nature that get in the way of perception and entrap us in a

citadel of abstractions. The scientific picture of nature presents us with a

simulacra of the natural world based on a preoccupation with evolution and the

classification of animals. The museum display of stuffed lions and zebras, with

a painted backdrop, tells the museum visitor more about the art of taxidermy

than it does about the African Savanna.

Seeking to experience untamed nature on her own terms, I

have had to leave the city and move out into the wilderness. The wilderness, or

what is left of it, has been pushed to the periphery of our world. Because it

seems indifferent or at times hostile to our plans, and because every authentic

encounter with nature tends to shatter our preconceptions, the wild has often

been vilified as savage and brutal. Though on one level the wilderness

experience is unsettling, on another level an elemental affinity with nature

calls to a wilderness within.

It is difficult living in the wilderness without in some way

transforming it and making it less wild. As soon as you enter the woods,

much of the wildlife retreats into burrows or dens, or deeper into the woods.

Often only in the still hours of dawn or sunset that you may see them reemerge.

But it is even more difficult trying to capture in paint the

diverse and chaotic complexity of the woods. As a classically trained

artist, whose teacher was a student of Pietro Annigoni, I spent many years

studying the painting of the masters of the Italian Renaissance and copying

classical sculptures to gain the insights from the past masters into the forms

and designs of nature. My classical training, which was based mostly on

the Italian School, taught students to see this “big picture”, and to leave out

those details that would destroy this larger truth. But as an artist, I have

often been overwhelmed by the richness and the diversity of nature. To

attempt capture all the subtleties of nature, “ rejecting nothing and

selecting nothing”, as John Ruskin demands seems an impossible task. Nor

could I hope to understand all the forms of nature, particularly because these

forms are constantly re-emerging in new growth and dissolving in decay of

amorphous shapes.

Every authentic experience of nature entails moving

past all mental images or memories. Even for an experienced artist, a

long time of looking must pass before mental images fade and perception can

occur. But once they do begin to break through mental images, many art

students tend to become fixated with detail, rather than relationships.

The more skilled the artist, the more nuanced his perception of the

relationships of shapes tones and colours.

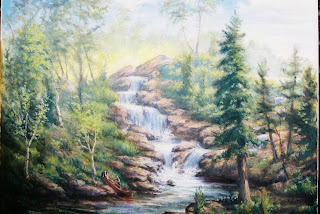

But how can an artist paint the wilderness, capturing all these

relationships of the experience and their inherent sense of form, without

returning to preconceptions. For painting the wilderness, I found in the

approach of the Macchiaioli the best. This approach to painting was not so

foreign from my artistic training. While studying in Italy, I studied the works

of the many Macchiaioli painters, including Filadelfo Simi, whose brother Renzo

was a mentor of Annigoni. This group of nineteenth century Italian artist

revived the Renaissance technique of painting splotches of stains of paint

(macchia) that defined the large chiaruscuro, or light dark pattern of the

painting, in order to counteract the rigid techniques of the academies.

This technique of drawing with colour directly on the canvas was originally use

by artists such a Titian and Caravaggio, for oil sketches or the early stages

of a painting. DaVinci’s use of sfumato (smoke like shadows) is a

specific example of the use of the macchiaioli principle.

Rather than being left in its first form, the macchia would

be gradually adjusted to take on the qualities, complexity, and mystery of

emerging forms that I found in the subject. According to its associations with

what surrounds it, a single macchia shape can take on a multiplicity of

functions: defining edges, creating textures, defining silhouettes or

gradations of tones or colour. Rather than beginning with some delineated

concept of form, the macchia enables the artist to explore and develop the

visual relationships that he finds in nature, without preconceptions. However,

this is not to say that the artist’s experience of nature is not informed by a

study of form, colour or optical illusions, but that preconceptions do not

stand in the way of perception.

Unlike impressionism, which remained subjective and

superficial, the macchiaioli approach to painting explored the emerging

relationships of forms and their relationships. These explorations begin with

plein air studies and oil sketches that for the artist become the interface of

his wilderness experience. These authentic experiences can then be recalled and

combined with other experiences of nature to create works that include symbolic

and poetic elements that express the artist experience of life in the

wilderness. Because few people have the time or opportunity to study

nature so closely, it becomes the vocation of the artist to lead them back to a

more primal experience of nature. .